Air pollution is the invisible killer, unseen but also unacknowledged on the death certificates of the 40,000 people it sends to an early grave in the UK every year. But on Wednesday, for the first time, the lethal impact of toxic air was given a name and a face – Ella Kissi-Debrah, a nine-year-old girl from south London.

Politicians have been told for many years that dirty air kills but have ducked the decisions needed amid the noisy honking of the motoring lobby. The coroner’s conclusion that air pollution was a cause of Ella’s death means those politicians can no longer pretend that illegal levels of pollution are a victimless crime.

The immediate impact will pile pressure on the government for an “Ella’s law” to lower the UK’s legal pollution limits to those recommended by the World Health Organization. The proposal is not only backed by Ella’s family, but by groups ranging from the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health to the Mumsnet website.

Many see it as a scandal that serious action to cut toxic air has not been taken already. Most urban areas of the UK have had illegal levels of diesel-driven nitrogen dioxide since 2010 and ministers have had their plan declared illegal three times. Small particle pollution is above WHO limits in many cities and towns.

A cross-party committee of MPs declared air pollution a “public health emergency” in 2016, while the WHO calls it “the new tobacco”. Over 90% of the world’s people breathe unclean air, and at least 7 million die early each year, with many more suffering damage to their health.

While air quality is improving in some parts of the world, scientific understanding of the insidious health impacts is expanding fast. Air pollution may be damaging every organ in the body, according to a comprehensive global review, with effects including heart and lung disease, diabetes, dementia, reduced intelligence and increased depression. Children and the unborn may suffer the most.

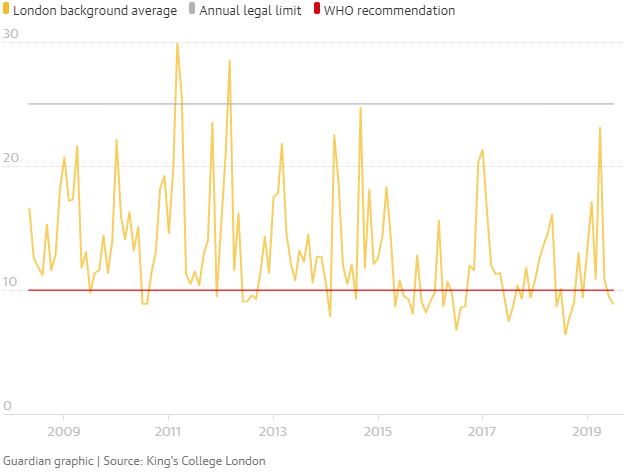

Current UK limits for particulate matter are two and a half times higher than the WHO recommends

PM2.5 in micrograms per cubic metre of air

In the UK, the government’s own analysis in 2017 identified by far the most effective action – clean air zones in urban centres where polluting vehicles are deterred, usually by charges. But ministers pushed the responsibility for introducing these on to local authorities, who are now delaying or abandoning their introduction, citing the temporary pollution cuts during coronavirus lockdowns. However, in many parts of the UK pollution has already returned to levels at or above pre-lockdown levels.

Experts said the coroner Philip Barlow’s verdict on Ella’s death was unlikely to have immediate legal consequences for the government or councils. “This was a decision about the cause of Ella’s death, rather than determining who was at fault, so it doesn’t provide a direct precedent others can rely on,” said Katie Nield, a lawyer at the environmental law charity ClientEarth.

However, the coroner explicitly cited the “levels of [air pollution] in excess of WHO guidelines” to which Ella was exposed before her death. Despite a previous commitment to putting WHO limits into UK law by the then environment minister, Michael Gove, Conservative MPs voted down the proposal in March, with the minister Rebecca Pow questioning its “economic viability”.

The coroner’s groundbreaking finding on Ella’s death makes this backsliding look politically untenable and a powerful coalition has formed behind the WHO target, including ClientEarth, which inflicted three court defeats against the government’s plans, the all-party parliamentary group on air pollution, led by Geraint Davies, and the British Safety Council.

The mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, who has overseen significant cuts in the capital’s air pollution, also wants greater national-level action. “Ministers and the previous mayor [Boris Johnson] acted too slowly in the past,” he has said. Further pressure may come next year when the coroner produces an official report to prevent future deaths based on Ella’s case.

Greg Archer, the UK director of the Transport and Environment campaign group and who gave expert evidence to the inquest, said: “Ella’s tragic death could have been avoided if irresponsible governments had not put the needs of the car industry and diesel car drivers before vulnerable children.”

“In the seven years since Ella died, nearly 250,000 other UK families have suffered tragedy as a result of vulnerable loved ones breathing toxic air – four times more than those killed by Covid this year,” Archer said. “In modern Britain, this is inexcusable and preventable.”

Paul Swinney, director of policy and research at the Centre for Cities, contrasted the climate emergencies declared by government and local authorities with their action on dirty air: “When it comes to local air pollution, something they have very clear control over, they don’t do anything [mainly] because the motorist lobby is very strong. But if we keep on ducking these things, we are going to see people continuing to die.”